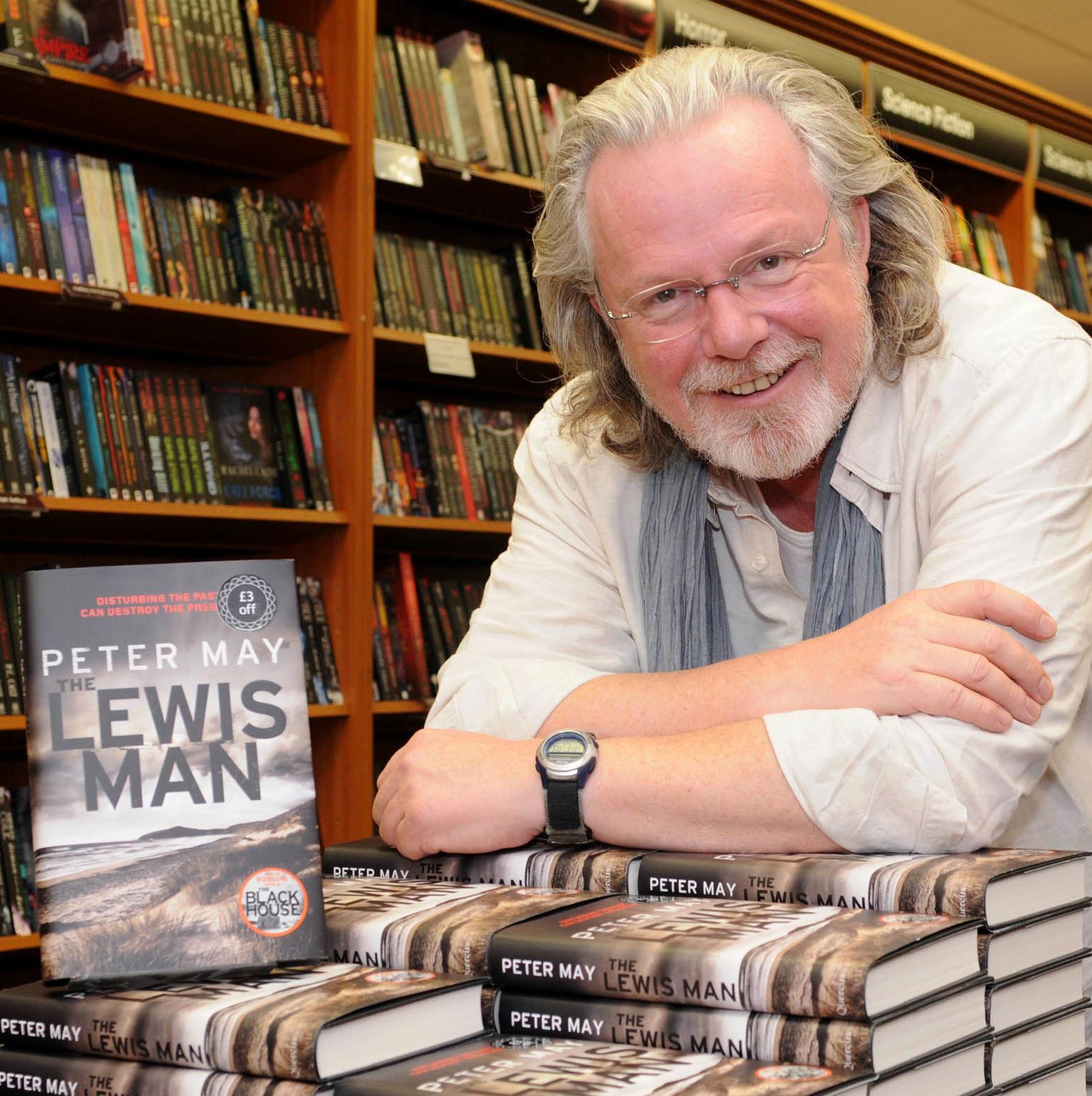

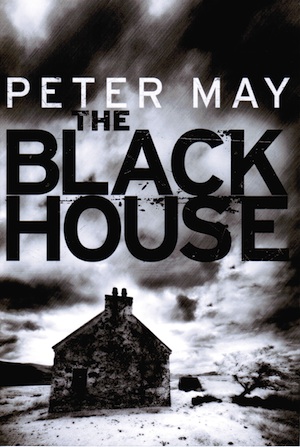

The

Blackhouse

PROLOGUE

They are just kids. Sixteen years old. Emboldened by alcohol, and hastened by the approaching Sabbath, they embrace the dark in search of love, and find only death.

Unusually, there is just a light wind. And for once it is warm, like breath on the skin, caressing and seductive. A slight haze in the August sky hides the stars, but a three-quarters moon casts its pale, bloodless light across the compacted sand left by the outgoing tide. The sea breathes gently upon the shore, phosphorescent foam bursting silver bubbles over gold. The young couple hurry down the tarmac from the village above, blood pulsing in their heads like the beat of the waves.

Off to their left, the rise and fall of the water in the tiny harbour breaks the moonlight on its surface, and they hear the creaking of small boats straining at ropes, the soft clunk of wood on wood as they jostle for space, nudging each other playfully in the darkness.

Uilleam holds her hand in his, sensing her reluctance. He has tasted the sweetness of the alcohol on her breath and felt the urgency in her kiss, and knows that tonight she will finally succumb. But there is so little time. The Sabbath is close. Too close. Just half-an-hour, revealed in a stolen glance at his watch before leaving the street lights behind.

Ceit is breathing rapidly now. Afraid, not of the sex, but of the father she knows will be sitting by the fire, watching the embers of the peat fade towards midnight, timed with a practised perfection to die before the coming day of rest. She can almost feel his impatience slow-burning to anger as the clock ticks towards tomorrow and she has not yet returned. How is it possible that things can have changed so little on this God-fearing island?

Thoughts crowd her mind, fighting for space with the desire which has lodged there, and the alcohol which has blunted her youthful resist- ance to it. Their Saturday night at the social club had seemed, just a few short hours ago, to stretch ahead to eternity. But time never passes so quickly as when it is in short supply. And now it is all but gone.

Panic and passion rise together in her chest as they slip past the shadow of an old fishing boat canted at an angle on the pebbles above the watermark. Through the open half of the concrete boatshed, they can see the beach beyond, framed by unglazed windows. The sea seems lit from within, almost luminous. Uilleam lets go of her hand and slides open the wooden door, just enough to allow them past. And he pushes her inside. It is dark here. A rank smell of diesel, and salt water and seaweed fill the air, like the sad perfume of hurried, pubescent sex. The dark shadow of a boat on its trailer looms above them, two small rectan- gular windows opening like peepholes on to the shore.

He pushes her up against the wall, and at once she feels his mouth on hers, his tongue forcing its way past her lips, his hands squeezing the softness of her breasts. It hurts, and she pushes him away. ‘Not so rough.’ Her breath seems to thunder in the darkness.

‘No time.’ She hears the tension in his voice. A male tension, filled at the same time with desire and anxiety. And she begins to have second thoughts. Is this really how she wants her first time to be? A few sordid moments snatched in the dark of a filthy boatshed?

‘No.’ She pushes him aside and steps away, turning towards the window and a breath of air. If they hurry there is still time to get back before twelve.

She sees the dark shape drift out of the shadows almost at the same moment she feels it. Soft and cold and heavy. She lets out an involuntary cry.

‘For God’s sake, Ceit!’ Uilleam comes after her, frustration added now to desire and anxiety, and his feet slide away from under him, for all the world as if he has stepped on ice. He lands heavily on his elbow and a pain shoots through his arm. ‘Shit!’ The floor is wet with diesel. He feels it soaking through the seat of his trousers. It is on his hands. Without thinking, he fumbles for the cigarette lighter in his pocket. There just isn’t enough damned light in here. Only as he spins the wheel with his thumb, sparking the flame, does it occur to him that he is in imminent danger of turning himself into a human torch. But by then it is too late. The light is sudden and startling in the dark. He braces himself. But there is no ignition of diesel fumes, no sudden flash of searing flame. Just an image so profoundly shocking it is impossible at first to comprehend.

The

man is hanging by his neck from the rafters

overhead, frayed orange plastic rope tilting his

head at an impossible angle. He is a big man,

buck naked, blue-white flesh hanging in folds

from his breasts and his buttocks, like a

loose-fitting suit two sizes too big. Loops of

something smooth and shiny hang down between his

legs from a gaping smile that splits his belly

from side to side. The flame sends the dead

man’s shadow dancing around the scarred and

graffitied walls like so many ghosts welcoming a

new arrival. Beyond him Uilleam sees Ceit’s

face. Pale, dark-eyed, frozen in horror. For a

moment he thinks, absurdly, that the pool of

diesel around him is agricultural, dyed red by

the Excise to identify its tax-free status –

before realizing it is blood, sticky and thick

and already drying brown on his hands.

chapter ONE

I

It was late, sultry warm in a way that it only ever gets at festival time. Fin found concentration difficult. The darkness of his small study pressed in around him, like big, black, soft hands holding him in his seat. The circle of light from the lamp on his desk burned his eyes, drawing him there like a moth, blinding now, so that he found it hard to keep his notes in focus. The computer hummed softly in the stillness, and its screen flick- ered in his peripheral vision. He should have gone to bed hours ago, but it was imperative that he finish his essay. The Open University offered his only means of escape, and he had been procrastinating. Foolishly.

He heard a movement at the door behind him and swivelled angrily in his seat, expecting to see Mona. But his words of rebuke never came. Instead, he found himself looking up in astonishment at a man so tall that he could not stand upright. His head was tipped to one side to avoid the ceiling. These were not big rooms, but this man must have been eight feet tall. He had very long legs, dark trousers gathering in folds around black boots. A checked cotton shirt was tucked in at a belted waist, and over it he wore an anorak, hanging open, the hood falling away from an upturned collar. His arms dangled at his sides, big hands protruding from sleeves that were too short. To Fin he looked about sixty, a lined, lugubrious face with dark, expressionless eyes. His silver-grey hair was long and greasy and hung down below his ears. He said nothing. He just stood staring at Fin, deep shadows cut in stony features by the light on Fin’s desk. What in the name of God was he doing there? All the hair on Fin’s neck and arms stood on end, and he felt fear slip over him like a glove, holding him in its grasp.

And then somewhere in the distance he heard his own voice wailing, childlike, in the dark. ‘Funny ma-an . . .’ The man remained staring at him. ‘There’s a funny ma-an . . .’

‘What is it, Fin?’ It was Mona’s voice. She was alarmed, shaking him by the shoulder.

And even as he opened his eyes and saw her frightened face, perplexed and still puffy from sleep, he heard himself wail, ‘Funny ma-an . . .’

‘For God’s sake, what’s wrong?’

He turned away from her on to his back, breathing deeply, trying to catch his breath. His heart was racing. ‘Just a dream. A bad dream.’ But the memory of the man in his study was still vivid, like a childhood nightmare. He glanced at the clock on the bedside table. The digital display told him it was seven minutes past four. He tried to swallow, but his mouth was dry, and he knew that he would not get back to sleep.

‘You just about scared the life out of me.’

‘I’m sorry.’ He pulled back the covers and swung his legs down to the floor. He closed his eyes and rubbed his face, but the man was still there, burned on his retinas. He stood up.

‘Where are you going?’

‘For a pee.’ He padded softly across the carpet and opened the door into the hall. Moonlight fell across it, divided geomet- rically by ersatz Georgian windows. Halfway down the hall he

passed the open door of his study. Inside, it was pitch-black, and he shuddered at the thought of the tall man who had invaded it in his dream. How clear and strong the image remained in his mind. How powerful the presence had been. At the bathroom door he paused, as he had every night for nearly four weeks, his eyes drawn to the room at the end of the hall. The door stood ajar, moonlight washing the space beyond it. Curtains that should have been drawn but weren’t. It contained only a terrible emptiness. Fin turned away, heart sick, a cold sweat breaking out across his forehead.

The splash of urine hitting water filled the bathroom with the comforting sound of normality. It was always with silence that his depression came. But tonight the usual void was occu- pied. The image of the man in the anorak had displaced all other thoughts, like a cuckoo in the nest. Fin wondered now if he knew him, if there was something familiar in the long face and straggling hair. And suddenly he remembered the descrip- tion Mona had given the police of the man in the car. He had been wearing an anorak, she thought. Had been about sixty, with long, greasy, grey hair.

The

Lewis Man

PROLOGUE

On this storm-lashed island three hours off the north-west coast of Scotland, what little soil exists gives the people their food and their heat. It also takes their dead. And very occasionally, as today, gives one up.

It is a social thing, the peat cutting. Family, neighbours, chil- dren, all gathered on the moor with a mild wind blowing out of the south-west to dry the grasses and keep the midges at bay. Annag is just five years old. It is her first peat cutting, and the one she will remember for the rest of her life.

She has spent the morning with her grandmother in the kitchen of the crofthouse watching eggs boil on the old Enchantress stove, fired by last year’s peat. Now the women head out across the moor carrying hampers, Annag barefoot, the bog’s brown waters squishing between her toes as she runs ahead over prickly heather, trans- ported by the excitement of the day.

The sky fills her eyes. A sky torn and shredded by the wind. A sky that leaks sunlight in momentary flashes to spill across dead grasses where the white tips of bog cotton dip and dive in frantic eddies of turbulent air. In the next days the wild flowers of spring and early summer will turn the brown winter wastes yellow and purple, but for the moment they remain dormant, dead. In the distance, the silhouettes of half a dozen men in overalls and cloth caps can be seen against the dazzle of sunlight flashing across an ocean that beats against cliffs of black, obdurate gneiss. It is almost blinding, and Annag raises her hand to shade her eyes to see them stoop and bow as the tarasgeir slides through soft black peat to turn it out in sodden square slabs. The land is scarred by generations of peat cutting. Trenches twelve or eighteen inches deep, with fresh-cut turfs laid along the tops of them to dry on one side and then the other. In a few days the cutters will return for the cruinneachadh, the gathering of the peats into rùdhain, small triangular piles that allow the wind to blow between them and complete the drying.

In time they will be collected in a cart and taken back to the croft, dry brittle peats laid like bricks, one upon the other, in a herring-bone pattern, to construct the stack that will keep the family warm and cook the food that will fill their bellies all next winter.

It is how the people of the Isle of Lewis, this northernmost island in the Scottish Hebridean archipelago, have survived for centuries. And in this time of financial uncertainty, as the cost of fuel soars, those with open hearths and stoves have returned in droves to the traditions of their ancestors. For here the only cost of heating your home is the expenditure of your labour and your devotion to God.

But for Annag it is just an adventure, out here on the wind- blasted moor with the soft air filling her mouth as she laughs and calls out to her father and grandfather, the voices of her mother and grandmother in shouted conversation somewhere behind her. She has no sense at all of the tension that has caught the little clutch of peat cutters ahead of her. No way, from her limited experience, of reading the body language of the men crouched down around the stretch of trench wall that has collapsed about their feet.

Too late her father sees her coming and shouts at her to stay back. Too late for her to stop her forward momentum, or respond to the panic in his voice. The men stand suddenly, turning towards her, and she sees her brother’s face the colour of cotton sheets laid out in the sun to bleach.

And she follows his eyes down to the fallen peat bank and the arm that lies stretched out towards her, leathery skin like brown parchment, fingers curled as if holding an invisible ball. One leg lies twisted over the other, a head tipped towards the ditch as if in search of a lost life, black holes where the eyes should have been.

For a

moment she is lost in a sea of incomprehension,

before realisation washes over her, and the

scream is whipped from her mouth by the wind.

CHAPTER ONE

Gunn saw the vehicles parked at the roadside from some distance away. The sky was black and blue, brooding, contused, rolling in off the ocean low and unbroken. The first spits of rain were smeared across his windscreen by the intermittent passage of its wipers. The pewter of the ocean itself was punctuated by the whites of breaking waves ten or fifteen feet high, and the solitary blue flashing light of the police car next to the ambulance was swallowed into insignificance by the vastness of the landscape.

Beyond the vehicles, the harled houses of Siader huddled against the prevailing weather, expectant and weary, but accustomed to its relentless assault. Not a single tree broke the horizon. Just lines of rotting fenceposts along the road- side, and the rusting remains of tractors and cars in deserted yards. Blasted shrubs showing brave green tips clung on with stubborn roots to thin soil in anticipation of better days to come, and a sea of bog cotton shifted in ripples and currents like water in the wind.

Gunn parked beside the police car and stepped out into the blast. Thick dark hair growing back in a widow’s peak from a furrowed forehead was whipped into the air, and he gathered his black quilted anorak around him. He cursed the fact that he had not thought to bring a pair of boots, and stepped at first gingerly through the soft ground, before feeling the chill of the bog water seeping into his shoes and soaking through his socks.

He reached the first of the peat banks, and followed a path along the top of it, skirting the clusters of drying turfs. The uniforms had hammered metal stakes into soft ground to mark off the site with blue and white crime- scene tape that hummed and twisted, fibrillating in the wind. The smell of peat smoke reached him from the nearest crofthouses some half a mile away out towards the edge of the cliffs.

A group of men stood around the body almost leaning into the wind, the fluorescent yellow of ambulance men waiting to take it away, policemen in black waterproofs and chequered hats who thought they had seen it all before. Until now.

They parted wordlessly to let Gunn through, and he saw the police surgeon crouched down, leaning over the corpse, delicately brushing aside crumbling peat with latexed fingers. He looked up as Gunn loomed overhead, and Gunn saw for the first time the brown, withered skin of the dead man. He frowned. ‘Is he . . . coloured?’

‘Only by the peat. I’d say he was a Caucasian. Quite young. Late teens or early twenties. A classic bog body, almost perfectly preserved.’

‘You’ve seen one before?’

‘Never. But I’ve read about them. It’s the salt carried in the wind from the ocean that allows the peat moss to thrive here. And when the roots rot it creates acid. The acid preserves the body, almost pickling it. His organs should be virtually intact inside.’

Gunn gazed with unabashed curiosity at the almost mummified remains. ‘How did he die, Murdo?’

‘Violently, by the looks of it. There appear to be several stab wounds in the area of the chest, and his throat has been cut. But it’ll take the pathologist to give you a defin- itive cause of death, George.’ He stood up and peeled off his gloves. ‘Better get him out of here before the rain comes.’

Gunn nodded, but couldn’t take his eyes off the face of the young man locked in the peat. Although there was a shrivelled aspect to his features, they would be recognis- able to anyone who knew him. Only the soft, exposed tissue of the eyes had decomposed. ‘How long’s he been here?’

Murdo’s laugh was lost in the wind. ‘Who knows? Hundreds, of years, maybe even thousands. You’ll need an expert to tell you that.’

The

Chessmen

PROLOGUE

He sits at his desk, grey with fear and the weight of this momen- tous step that, once taken, cannot be taken back. Like time and death.

The pen trembles in his hand as he writes.

This has been on my mind for some time. I know most people will not understand why, especially those who love me, and whom I also love. All I can say is that no one knows the hell I have lived through. And these last weeks it has become, simply, unbearable. It is time for me to go. I am so sorry.

He signs his name. The usual flamboyant scrawl. Illegible. And folds the note, as if in hiding the words he can somehow make them go away. Like a bad dream.

Like the step he is about to take into darkness.

He rises now, and looks around his room for the last time, wondering if he really has the courage to go through with it. Should he leave the note or should he not? Will it really make any difference?

He glances at it, fallen open now, and propped against the computer screen where he hopes it will be obvious. The pain of regret fills his heart as his eye follows the looping letters he learned to write all those years before when his whole life still lay ahead of him. A bitter- sweet recollection of innocence and youth. The smell of chalk dust and warm school milk.

How

pointless it all has been!

CHAPTER ONE

When Fin opened his eyes the interior of the ancient stone dwelling that had sheltered them from the storm was suffused with a strange pink light. Smoke drifted lazily into the still air from the almost dead fire, and Whistler was gone.

Fin raised himself up on to his elbows and saw that the stone at the entrance had been rolled aside. Beyond it he could see the rose-tinted mist of dawn that hung over the mountains. The storm had passed. Its rain had fallen, and it had left in its wake an unnatural stillness.

Painfully, Fin unravelled himself from his blankets and crawled past the fire to where his clothes were spread out across the stone. There was a touch of dampness in them still, but they were dry enough to put on again, and he lay on his back and wriggled into his trousers before sitting up to button his shirt and drag his jumper over his head. He pulled on his socks and pushed his feet into his boots, then crawled out on to the mountainside without bothering to lace them up.

The sight that greeted him was almost supernatural. The mountains of south-west Lewis rose steeply all around, disap- pearing into an obscurity of low clouds. The valley below seemed wider than it had in the lightning of the night before.

The giant shards of rock that littered its floor grew like spec- tres out of a mist that rolled up from the east, where a not yet visible sun cast an unnaturally red glow. It felt like the dawn of time.

Whistler stood silhouetted against the light beyond the collection of broken shelters they called beehives, on a ridge that looked out over the valley, and Fin stumbled over sodden ground with shaking legs to join him.

Whistler neither turned nor acknowledged him. He just stood like a statue frozen in space and time. Fin was shocked by his face, drained as it was of all colour. His beard looked like black and silver paint scraped on to white canvas. His eyes dark and impenetrable, lost in shadow.

‘What is it, Whistler?’

But Whistler said nothing, and Fin turned to see what he was staring at. At first, the sight that greeted him in the valley simply filled him with confusion. He understood all that he saw, and yet it made no sense. He turned and looked back beyond the beehives to the jumble of rock above them, and the scree slope that rose up to the shoulder of the moun- tain where he had stood the night before and seen lightning reflected on the loch below.

Then he turned back to the valley. But there was no loch. Just a big empty hole. Its outline was clearly visible where, over eons, it had eaten away at the peat and the rock. Judging by the depression it had left in the land, it had been perhaps a mile long, half a mile across, and fifty or sixty feet deep. Its bed was a thick slurry of peat and slime peppered by boul- ders large and small. At its east end, where the valley fell away into the dawn mist, a wide brown channel, forty or fifty feet across, was smeared through the peat, like the trail left by some giant slug.

Fin glanced at Whistler. ‘What happened to the loch?’ But Whistler just shrugged and shook his head. ‘It’s gone.’ ‘How can a loch just disappear?’

For a long time Whistler continued to stare out over the

empty loch like a man in a trance. Until suddenly, as if Fin had only now spoken, he said, ‘Something like it happened a long time ago, Fin. Before you or I were born. Sometime back in the fifties. Over at Morsgail.’

‘I don’t understand. What do you mean?’ Fin was filled with confusion.

‘Same thing. Postie used to pass a loch on the track between Morsgail and Kinlochresort every morning. Way out in the middle of bloody nowhere, it was. Loch nan Learga. So one morning, he’s coming down the track as usual, and there’s no loch. Just a big hole where it used to be. I’ve passed it many times myself. Caused a hell of a stir back then, though. The newspaper and television people came all the way up from London. And the things they speculated on . . . well, they seem crazy now, but they filled the airwaves and the column inches of the papers at the time. The favourite was that the loch had been hit by a meteor and evaporated.’

‘And what had happened?’

Whistler lifted his shoulders then dropped them again. ‘Best theory is that it was a bog burst.’

‘Which is what?’

Whistler made a moue with his lips, his eyes still drawn to the slime-filled basin of the disappeared loch. ‘Well . . . it can happen when you get a long spell without rain. Not very common here.’ He nearly smiled. ‘The surface peat dries up and cracks. And as any peat cutter knows, once it’s dry the peat becomes impervious to water.’ He nodded towards where the giant slug trail led off into the mist. ‘There’s another loch down there, lower in the valley. If I had any money, I’d put it on this one having drained down into the other.’

‘How?’

‘Most of these lochs sit on peat lying over Lewisian gneiss. Quite often they’re separated by ridges of something less stable, like amphibolite. When the dry spell is followed by heavy rain, like last night, the rainwater runs through the cracks in the peat creating a layer of sludge above the bedrock. Chances are that what happened here is that the peat between the lochs simply slid away on the sludge, the weight of the water in the upper loch burst through the amphibolite, and the whole bloody lot drained down the valley.’

There was a stirring of air as the sun edged a little higher, and the mist lifted just a touch. Enough to reveal something white and red catching the light at what must have been the deepest part of the loch.

‘What the hell’s that?’ Fin said, and when Whistler made no reply, ‘Do you have binoculars?’

‘In my rucksack.’ Whistler’s voice was little more than a breath.

Fin hurried back to their beehive and crawled inside to find Whistler’s binoculars. When he got out to the ridge again, Whistler hadn’t moved. He continued to stare impas- sively at the hole where the loch had once been. Fin raised the binoculars to his eyes and adjusted the lenses until the red and white object came clearly into focus. ‘Jesus!’ he heard himself whisper, quite involuntarily.

It was a small, single-engined aircraft, cradled among a cluster of boulders, and lying at a slight angle. It appeared to be pretty much intact. The windows of the cockpit were opaque with mud and slime, but the red and white of the fuselage was clearly visible. As were the black-painted letters of its call-sign:

G-RUAI

Fin felt every hair on the back of his neck stand up. RUAI, short for Ruairidh, the Gaelic for Roderick. A call-sign that had been in every newspaper for weeks seventeen years before, when the plane went missing, and Roddy Mackenzie with it.

Mist lifted off the mountains like smoke, tinted by the dawn. It was perfectly still. Not a sound broke the silence. Not even a birdcall. Fin lowered Whistler’s binoculars. ‘You know whose plane that is?’

Whistler nodded.

‘What the hell’s it doing here, Whistler? They said he filed a flight plan for Mull and disappeared somewhere out at sea.’

Whistler shrugged, but made no comment.

Fin said, ‘I’m going down to take a look.’

Whistler caught his arm. There was an odd look in his

eyes. If Fin hadn’t known better he would have said it was fear. ‘We shouldn’t.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s none of our business, Fin.’ He sighed. A long, grim breath of resignation. ‘I suppose we’ll have to report it, but we shouldn’t get involved.’

Fin looked at him hard and long, but decided not to ask. He pulled his arm free of Whistler’s grasp and said again, ‘I’m going down to take a look. You can come with me or not.’ He thrust the binoculars back into Whistler’s hands and started off down the hill towards the empty basin.

The climb was steep and difficult, over broken rock and hardened peat made slick by grasses washed flat by the rain. Boulders lined the banks of what had once been the loch, and Fin slithered over them, struggling to keep his feet and his balance, using his arms to stop himself falling. Down, down into the bowels of the one-time loch, wading through mud and slime, up to his knees at times, between rocks he used like stepping stones to cross the vast depression.

He had almost reached the plane before he turned to look back and see Whistler following just a few yards behind. Whistler stopped, breathing heavily, and the two men stood looking at each other for almost a full minute. Then Fin glanced beyond him, up through layers of peat and stone like the contour lines on an ordnance survey map, towards what just twelve hours before had been the shoreline. Had the loch still been there, the two men would have been fifty feet underwater by now. He turned to cover the remaining yards to the plane.

It was canted at the slightest of angles amid the shambles of rock and stone at the bottom of the loch, almost as if it had been placed there by the delicate hand of God. Fin was aware of Whistler’s breathing at his side. He said, ‘You know what’s weird?’

‘What?’ Whistler didn’t really sound like he wanted to know.

‘I can’t see any damage.’

‘So?’

‘Well, if the plane had crashed into the loch it would be

pretty smashed up, right?’

Whistler made no comment.

‘I mean look at it. There’s barely a dent on it. All the

windows are intact. The windscreen’s not even broken.’

Fin clambered over the last few rocks and pulled himself, slithering, up on to the nearest wing. ‘Not much rust in evidence either. I guess it must be mostly aluminium.’ He didn’t trust himself to stand on the treacherously slippery surface of the wing, and crawled on his hands and knees towards the nearside cockpit door. The window was thick with green slime and it was impossible to see inside. He grasped the handle and tried to pull it open. It wouldn’t

budge.

‘Leave it, Fin,’ Whistler called to him from down below. But Fin was determined. ‘Come up here and give me a

hand.’

Whistler didn’t move.

‘For Christ’s sake, man, it’s Roddy in there!’

‘I don’t want to see him, Fin. It would be like desecrating

a grave.’

Fin shook his head and turned back to the door, bracing

his feet against the fuselage on either side and pulling with all his strength. Suddenly it gave, with a loud rending like the sound of tearing metal, and Fin fell backwards on to the wing. Daylight flooded the interior of the cockpit for the first time in seventeen years. Fin scrambled back to his knees and grabbed the frame of the door to pull himself up to see inside. He heard Whistler hoisting himself on to the wing behind him, but didn’t turn. The sight that greeted him was shocking, his olfactory senses assailed by a stink like rotting fish.

The fascia below the windscreen arched across the cockpit, a mass of gauges and dials, glass smeared and muddied, inte- rior faces discoloured by water and algae. The passenger or co-pilot’s seat, at the nearside, was empty. The red, black and blue knobs of the throttle controls between the seats were still visible, drawn back to their idle position. The remains of a man was strapped into the pilot’s seat at the far side. Time and water and bacteria had eaten away all the flesh, and the only thing holding the skeleton together were the blanched remains of tendons and tough ligaments that had not decayed in the cold water temperatures. His leather jacket was more or less intact. His jeans, though bleached of colour, had also survived. His trainers, too, although Fin could see that the rubber was swollen, distending the shoes around what was left of the feet.

The larynx, ears and nose had all lost their structure, and the skull was plainly visible, a few strands of hair clinging to the remnants of soft tissue.

All of which was shocking enough to the two old friends who remembered the young, talented, restless Roddy with his shock of fair curly hair. But what disturbed them most was the terrible damage inflicted to the right side of the face and rear of the skull. Half the jaw appeared to be missing, exposing a row of yellowed broken teeth. The cheek- bone and upper part of the skull were smashed beyond recognition.

‘Jesus Christ.’ Whistler’s voice came to Fin in a blasphemous breath.

It had only taken a moment to absorb the scene exposed by the opening of the door, and Fin recoiled involuntarily almost immediately, banging the back of his head against Whistler’s shoulder. He slammed the door shut and turned around to slide down into a sitting position against it. Whistler crouched on his hunkers looking at him with wide eyes.

‘You’re right,’ Fin said. ‘We shouldn’t have opened it.’ He looked at Whistler’s face, so pale that pockmarks Fin had never before noticed, were visible now, the result perhaps of some bout of childhood chickenpox. ‘But not because we’re desecrating a grave, Whistler.’

Whistler frowned. ‘Why then?’

‘Because we’re disturbing a crime scene.’

Whistler gazed at him for several long moments, dark eyes

obscured by confusion, before he turned to slither down off the wing and make his way back towards the shoreline, climbing steadily out of the crater and back up towards the beehives.

‘Whistler!’ Fin called after him, but the big man didn’t even break stride and never looked back.